Ever heard the phrase, “There’s an app for that”? That’s true for apps for Deaf people as well.

Here, we share 12 of the best apps for Deaf people. This includes a video chat app for the Deaf, communication and alarm clock apps, as well as apps to help hearing people communicate in — and learn — sign language. Many are great for hard-of-hearing individuals too. (For other hearing loss apps, including captioning apps, read The Best Hearing Loss Apps of 2025.)

Included here:

ntouch | Sorenson VRS for Zoom | Hand Talk | Cardzilla | Make It Big (iOS) | Make it Big (Android) | Marco Polo | Ava | Microsoft Translator | ASL Dictionary | Lingvano | Sorenson Wavello

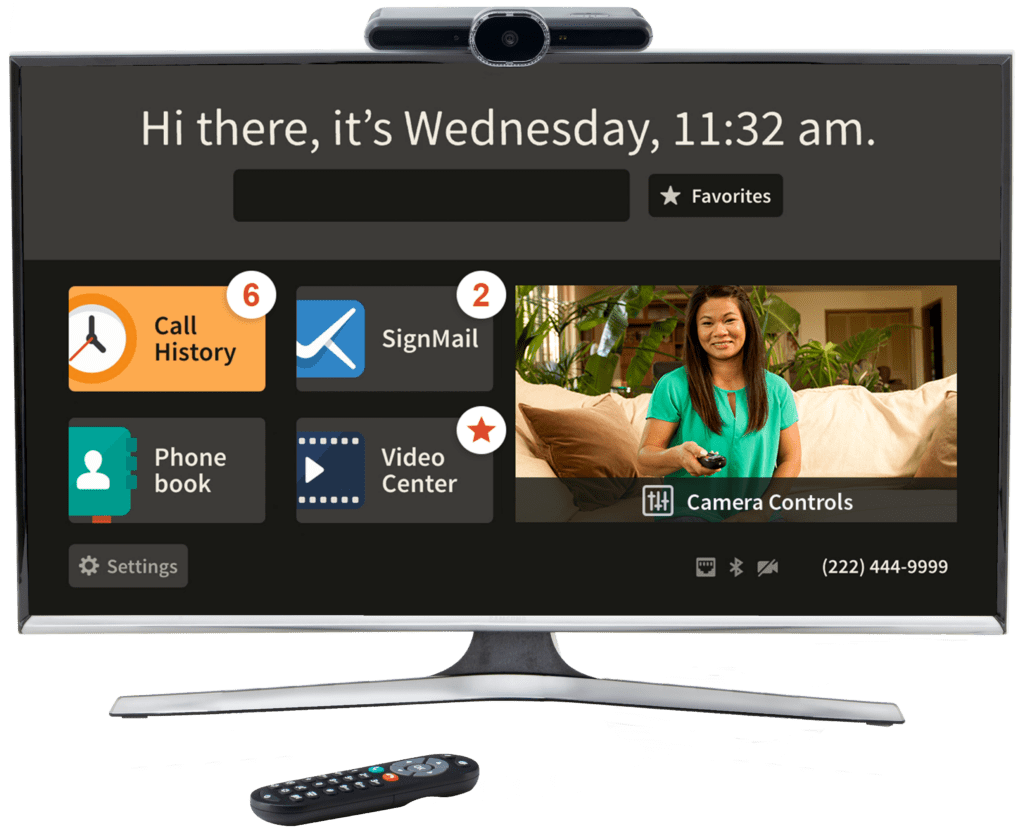

1. ntouch® by Sorenson

Cost: $0

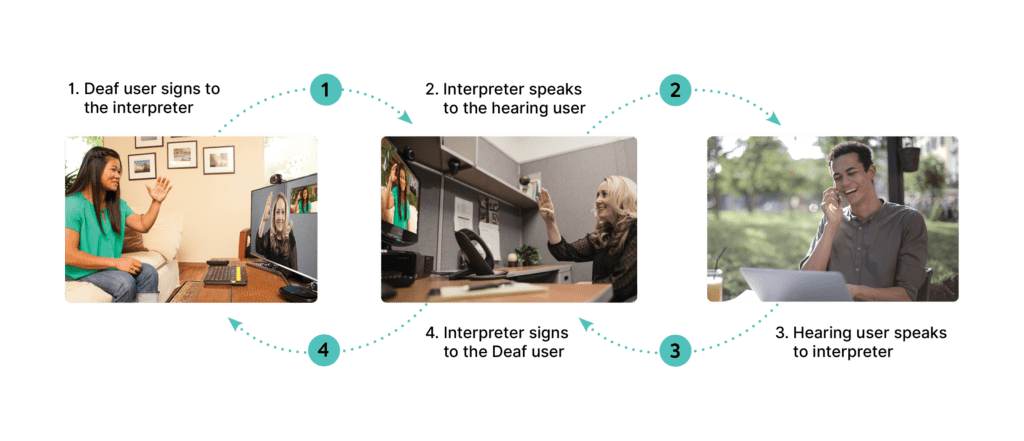

If you’re Deaf or hard-of-hearing and use sign language to communicate, you can register for VRS from Sorenson and use ntouch on your mobile phone. Federal funding covers the cost of the service, which is available only to qualified individuals.

While videophones are great solutions for at-home use, the world is increasingly mobile today.

ntouch solves that by turning your smartphone or laptop into a videophone, so you can make video relay calls anytime, anywhere.

All you need to make calls at home, work, school, or on the go is a Sorenson VRS account and smartphone, videophone, or computer. You can even make 911 calls in ASL. Every call is encrypted, so your privacy is protected.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.4 out of 5 stars

Rating from Apple App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.1 out of 5 stars

2. Sorenson VRS for Zoom

Cost: $0

If you’re Deaf or hard-of-hearing and use sign language to communicate, you can register for a no-cost VRS account with Sorenson.

Sorenson VRS for Zoom makes it easier than ever for a Deaf individual to attend a Zoom meeting and communicate in a group conversation with people who don’t know ASL.

Sorenson VRS for Zoom is not a traditional smartphone app. There are two ways to access it:

- Download the app in Zoom via the Zoom Marketplace on a desktop running MacOS or Windows. It requires that the host have a Sorenson VRS account and a paid Zoom account.

- Use the web app on any device that can access the internet and has a browser, such as a smartphone.

Both options let you dial in to Sorenson VRS directly through Zoom when the meeting is hosted on a paid account.

Note that Sorenson VRS for Zoom cannot be used for webinars.

Learn more about Sorenson VRS for Zoom and/or the web app.

3. Hand Talk Translator

Cost: $0 with ads; in-app purchases available

Originally built to translate between Portuguese and Brazilian Sign Language (Libras), Hand Talk Translator is now expanding into American Sign Language (ASL) with a beta version. It can automatically translate text and audio into a 3D avatar signing in ASL.

Because the ASL version is still in beta, the translations aren’t always perfect — for example, some words may be fingerspelled more often than signed. The app is actively improving, and user feedback is helping shape its growth.

Hand Talk can be a handy option for quick, basic communication when no interpreter is available. In some situations, it can also work as an alternative to a captioning app. It’s also a creative tool for anyone learning sign language, or for mixed Deaf-hearing households looking for another way to connect.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

3.6 out of 5 stars

Rating from Apple App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

3.8 out of 5 stars

4. Cardzilla

Cost: $0

Cardzilla by Tim Kettering for iOS or Randall Noriega for Android lets you easily convert messages into large text. No scrolling needed — your words resize automatically to fill the screen as you type. The app also saves your messages, and you can clear them with a simple shake. Navigation is easy with quick swipes.

Cardzilla supports Dark Mode, lets you customize colors, and even works with an attached keyboard. Best of all, the app is Deaf-owned and designed.

A Sorenson staffer shared, “I use Cardzilla more frequently for conversations than Make it Big. It’s more convenient in that I can shake off text and keep typing. It makes for a more dynamic conversation.”

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4 out of 5 stars

Rating from Apple App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.6 out of 5 stars

5. Make It Big for iPhone

Cost: $0

Make It Big by An Trinh turns typed text into large words that fill the entire screen. If you’re Deaf and need to talk with someone who doesn’t know ASL, you can type your message and show it to them without handing over your phone. They can also type back, making it easy to have a two-way conversation.

The app works in portrait and landscape mode. If you shake your phone, the background color and text change to create a flashing effect — perfect for when you need to get someone’s attention.

You can also customize the app with options like font size, text and background colors, flash on/off, and flash speed.

Rating from Apple App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.8 out of 5 stars

6. Make It Big for Android

Cost: $0 with ads; in-app purchases available

Make it Big for Android by Cazimir Roman is different from the Make It Big app for iPhone.

This app turns written text into large words on your screen. Think of it as an easy alternative to paper/pen or a captioning app when you just need to show short messages.

Make it big for Android automatically resizes what you type to fill the screen, which means it’s limited to shorter sentences.

You can customize the background and font, save text, and search saved texts. It supports offline use, dark mode, emojis, and multiple languages.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.4 out of 5 stars

Note: A newer version of the app does enable deleting entire text selections.

7. Marco Polo

Cost: $0 with in-app purchases available

Marco Polo from Joya Communications is not a live-call app, but a video messaging app that allows you to send and receive videos in group chats or one-on-one chats.

You can customize your messages with video filters, emoji reactions, voice effects, and drawing tools.

The app lets you send unlimited video messages for free. Paid plans are also available in-app for premium features like speed control and custom emojis.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.6 out of 5 stars

Rating from the App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.8 out of 5 stars

8. Ava Live Captions

Cost: $0 with in-app purchases available

Ava Live Captions from Ava Accessibility is a speech-to-text transcribing app. It “breaks down communication barriers between Deaf and hearing worlds with total access to real-time conversations, ensuring 24/7 accessibility.”

The app is free, but sessions are limited to 40 minutes. Ava offers longer sessions with paid plans available in the app.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.3 out of 5 stars

Rating from the App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.4 out of 5 stars

9. Microsoft Translator

Cost: $0

Microsoft Translator from Microsoft Corporation is an app that allows you to communicate with someone who uses a different language. This app translates not just speech, but also text, images, and group conversations in over 100 languages.

This means that it will translate not just speech, but also, for example, menus or road signs in a foreign language.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.4 out of 5 stars

Rating from Apple App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.8 out of 5 stars

10. ASL Dictionary

Cost: $4.99 - $9.99

ASL Dictionary by Software Studios isn’t designed for Deaf users — it’s built for the hearing people in their lives. The app includes 5,000 words and videos that demonstrate how to sign them. When a word has more than one sign or meaning, the app shows the different options.

Learners can test themselves with quizzes and play videos in slow motion or on a loop to practice at their own pace. The app has no sound, keeping the focus fully on ASL. The developer is also responsive to feedback, showing a commitment to improving the app over time.

There are two versions on each store: non-HD and HD. Both non-HD versions are $4.99. The HD version on Google Play is $7.99 and the HD version on iOS is $9.99.

The ratings below are for the HD versions.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.5 out of 5 stars

Rating from Apple App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.7 out of 5 stars

11. Lingvano

Cost: $0 with in-app purchases available

Lingvano by Lingvano GmbH is an app for learning American Sign Language (ASL). It is “the perfect starting point for beginners, with video lessons made by Deaf teachers that can be done anywhere, anytime. You’ll start signing in your very first lesson and can become conversational with just 10 minutes/day of practice!”

Lingvano also has lessons for British Sign Language (BSL) and Austrian Sign Language/Österreichische Gebärdensprache (ÖGS).

It is subscription-based, with monthly, quarterly, and yearly options for both ASL and BSL, and a quarterly option for ÖGS.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.8 out of 5 stars

Rating from Apple App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.9 out of 5 stars

12. Sorenson Wavello

Cost: $0

The Sorenson Wavello app is for your hearing friends and family. With Wavello installed on their cell phones — and built into Sorenson ntouch apps and Lumina VP — you can call them for a video chat using a VRS interpreter. Once the Wavello call is established, you can see the interpreter AND the person you are talking to on the screen at the same time.

Note that hearing friends and family can’t place Wavello calls. The Deaf VRS account holder must initiate the call.

Rating from Google Play

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.4 out of 5 stars

Rating from Apple App Store

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4.4 out of 5 stars

Kynesha Hicks, PAH Video Interpreter/SCIS Interpreter

Kynesha Hicks, PAH Video Interpreter/SCIS Interpreter Pamela Smith, Video Interpreter

Pamela Smith, Video Interpreter Robert Feggins, Video Interpreter

Robert Feggins, Video Interpreter Valerie McMillan, Regional Trainer

Valerie McMillan, Regional Trainer Ashly Drumwright, Video Interpreter

Ashly Drumwright, Video Interpreter Angela Littleton, Video Interpreter

Angela Littleton, Video Interpreter Dr. Teela Davis-Umukoro, Video Interpreter

Dr. Teela Davis-Umukoro, Video Interpreter