Black Deaf History Claims Space at Gallaudet University’s Center for Black Deaf Studies

February 27, 2023

Think fast:

Name two influential or famous Black people.

Now name two influential or famous Deaf people.

Next, name two influential or famous Black Deaf people.

That exercise gets more difficult with each step. Why is that?

Representation for Black, Deaf, and Black Deaf culture

Decades of advocacy have slowly, but surely gained traction to give due credit to Black contributions and accomplishments. Black History Month is now widely celebrated, spotlighting the role of Black people — individually and collectively — in our social and cultural development, spanning the arts, sciences, and political spheres. Still, broad recognition wanes every year when Black History Month ends.

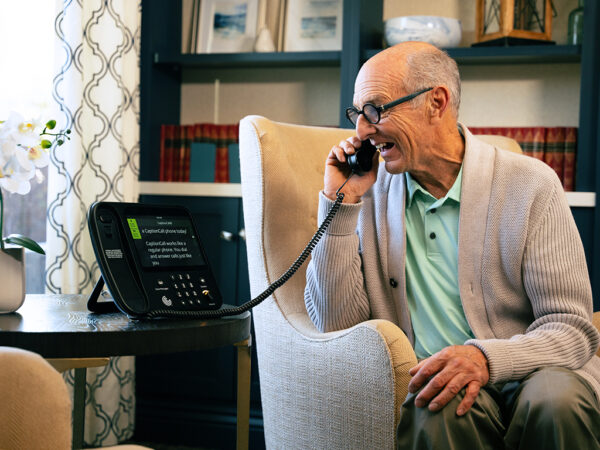

Deaf history-makers receive less mainstream attention, but momentum is building for greater Deaf visibility in media and DEIA spaces. Through greater availability of interpreting and captioning services and more consistent consideration of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility, more Deaf and hard-of-hearing people are staking their claim in shared public spaces. Sign language users are showing up in growing numbers in TV and movies, advertising, and social media.

Black Deaf individuals exist at the intersection of these identities and live an experience that is unique, overlapping, and historically absent from discussions and movements involving marginalized groups. That’s more than a minor oversight; representation matters, and generations of Black Deaf people have gone without it.

Spurring change with the Gallaudet Center for Black Deaf Studies

In 2020, Gallaudet University opened its Center for Black Deaf Studies, a turning point in documenting and sharing Black Deaf history and recognizing its significance in broader Deaf culture. The center was years in the making — a labor of love for national Black Deaf advocates like Dr. Carolyn McCaskill, a professor in the Deaf Studies program who serves as the center’s director.

In 2020, Gallaudet University opened its Center for Black Deaf Studies, a turning point in documenting and sharing Black Deaf history and recognizing its significance in broader Deaf culture. The center was years in the making — a labor of love for national Black Deaf advocates like Dr. Carolyn McCaskill, a professor in the Deaf Studies program who serves as the center’s director.

An advocate for Black Deaf visibility

Three years after the Gallaudet Center for Black Deaf Studies opened, Dr. McCaskill talked to us about what it means for the Black Deaf community and our collective knowledge of the rich history of Black Deaf culture. She talked to Sorenson’s Vice President of Brand Marketing, Ryan Commerson — a Gallaudet alumnus and former student of Dr. McCaskill — about the importance of the Center for Black Deaf Studies, Black ASL, and her own experiences:

Ryan: So, I want to say thank you, Dr. McCaskill, for meeting with us. Your reputation precedes you. I’ve known about you for a long time, I used to be your student.

Carolyn: Yes, we have, and I do remember you well.

Ryan: (laughing) Yeah, because I remember you telling us a little bit of, if you don’t mind telling us a little bit about the Center of Deaf Black Studies?

Carolyn: Sure. So, the Center for Black Deaf Studies, CBDS, in brief, was founded in the year 2020. It feels like we’ve been largely overlooked. In general, people don’t know much about our very rich history.

People do know American History in general, White History, people know Black Hearing History, and people know White Deaf History, but what people don’t know about, is Black Deaf history. And there’s very little information out there. Not much has been documented about our experiences, and when you go into libraries, you just don’t see much.

And I wanted the Center for Black Deaf Studies to really spotlight our history, and who were the contributors, and who were the people who had very important roles in our history? And so the Center for Black Deaf Studies serves as a place where…It’s a clearinghouse. Where people can reach out to us and inquire about Black Deaf teachers, and we can give names, and we can provide backgrounds, and we can explain where they’re from.

People reach out to us about Black Deaf artists, and we’re more than happy to share with them Black Deaf artists with the DEIA perspective, or Black Deaf business owners. You know, sure, we’re we’re happy to help with that. And so, we are a contact place for information for all of those types of things where access to information is available.

And I wanted the Center for Black Deaf Studies to support different cultural events, whether they be on campus, maybe sometimes in partnership with other organizations in supporting their work.

And I really wanted the Center for Black Deaf Studies to also serve as a place of research. There’s so much. There’s so much research that needs to be done, and Black ASL, the book that was published, I have it here, The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL, is one of three — well, I’m one of four authors for that book, and basically this is just a scratch on the surface. There are a lot of more important works that need to be done, and have yet to be done.

And so my hope is that we can encourage others to continue in their curiosity. I’m hoping to inspire people to want to continue this legacy, and if they want to research, I want to support them.

Bringing Black ASL to the forefront

Ryan: I remember your work some time ago when you were…basically you’re the pioneer, the trailblazer, for Black ASL, and so if you could elaborate a little bit more on that?

Carolyn: When it was time to have the discussion about what my dissertation would be about, I honestly had no idea, Ryan, of what it would be about. And it just so happens that I was in a conversation with my professor, Dr. Roz.

Ryan: Yes.

Carolyn: So we had a discussion about Black Deaf Schools and how we signed differently, and Dr. Roz had never heard me talk about this. Dr. Roz said, “Wait, you went to a Black Deaf school?” and I said, “Oh, yes, absolutely.” And they said, “Well, you have to write about it.” And I said, “Really?”

And I realized that through my lifetime, I had really suppressed my experiences. And I was ashamed of my history, quite embarrassed. And I think I felt embarrassed because I was never encouraged and supported to talk about it. And I didn’t really feel that anyone would be interested in hearing about my history.

And so, I got into an explanation about my history and they said, “Go for it!” And I said, “Really? Me?” And I said, “Okay, so how can I do this?”

And so, my dissertation committee had a discussion, and I told them, I said, “I think that I would be able to contact people that I would be able to interview.” And they said, “Go, go, do it, do it!” And so I did, and the rest is history.

And then I was able to defend my dissertation, and this is Dr. Cecil…

Ryan: Yeah, I remember them.

Carolyn: He happened to watch and was fascinated. And they came up to me and said, “Let’s work together.” And so we partnered, which was nice. The interpreting department at Gallaudet, and Linguistics Department, and Deaf Studies collaborated.

And so we wrote a grant, Spencer’s Foundation money. And so that money, in fact, helped me travel to six different states in the South doing several interviews. And that’s how I collected the data, and then published the book in 2011.

And so it is quite interesting that this book, being published in 2011, you know, we’ve gotten a lot more recognition as of lately, 2020, 2022, you know, 2023, and I think people are learning more and more about it, and they’re quite fascinated.

The Black Deaf Community itself is experiencing a joy that they’ve previously been ashamed about. And, you know, they’re like, wow, my language is beautiful. I’m empowered to be myself and it’s okay. And it’s okay that I say this and I talk like this and “my girls” and “my man” and this and that, and it’s like, yes, do that, do that.

And then we did a film. We did a film based on the book. And this film is a documentary called Signing Black in America.

(music playing)

And it’s now available on YouTube, and again, it’s called Signing Black in America. So, it’s really nice that we have that in conjunction with the book about Black ASL.

And people often ask me, you know, “Where can I take a class and learn, are there classes to learn Black ASL?” And I have to tell them, “I’m sorry, there are no classes available.”

Look, never say never. I do believe that a class will come up in the future, someone who’s really motivated and passionate about establishing classes, but as of now, there are no classes available. And yeah, no classes available on Black ASL.

Ryan: You’ve created a legacy, and your legacy will continue on, expanding through the times.

And now with this CBDS, you have a physical location where people can contact, get resources, go study various majors. The CBDS vision of what you can imagine, and seeing that an actual real life impact that this center has.

Carolyn: Yeah, what I will say first is that I’m really grateful. I’m extremely grateful to have had the opportunity because when I was a kid, I had no idea. I had no idea.

When I went to public school and my hearing began to worsen. I went to the School for the Deaf, Black Deaf School in Alabama, and I had no idea about what my future looked like.

I couldn’t think about going to Gallaudet. Are you kidding me? No way!

And so when I look back on this life that I’ve been on, this journey, I want this to be a place where parents, students, can feel inspired and moved to do something that they’ve always wanted. And so parents can support them in that. My mother, my mom, was a staunch supporter of me and my sisters, and my cousins, and I’m grateful for that.

And so getting back to what I envision for now, we’ve got a lot of work to do. But this March 28th, 29th and 30th, and April 2nd, we will be hosting our first ever Black Deaf Studies Symposium.

Ryan: Yes.

Carolyn: And this will be the first time that we’ve hosted this event.

Black Deaf scholars with advanced degrees

Ryan: How many Black Deaf people or individuals have a Ph.D.?

Carolyn: I would say back in 2005, I was number eight, but now when I think about Black Deaf individuals with PhDs, it’s about 30. So that number is increasing, more coming through the pipeline.

Ryan: It’s still small, but it’s still growing in comparison with the entirety of the rest of the world, but like you said, there is more work to do.

Carolyn: Absolutely.

What’s next for the Center for Black Deaf Studies

Ryan: And what are you hoping that the center is going to accomplish in the next, let’s say, two to three years?

Carolyn: My hope is that we continue to fundraise money that it takes to support the center.

We recently hired Lindsay, who is our first Black Deaf scholar researcher. And so we hired for that position, and so we continue to add more positions. And really, like I said earlier, there’s a lot more work that’s needing to be done. We need a videographer to document the oral history, and so we want to do that.

Ryan: So, the Center of Deaf Studies, and then there’s Black Deaf Studies. Could you elaborate a little bit more why there is value in having its own Center for Black Deaf Studies? You know, to follow that distinction from the other Deaf Studies.

Carolyn: Well, I’m happy you asked Ryan, because I didn’t mention it to you, but last year we finally founded, established a Black Deaf Studies minor at Gallaudet.

Ryan: Oh, I didn’t know that.

Carolyn: We did. We finally established that, and that was based on the student population expressing their interest and desire.

Many students said they come into Gallaudet, and Gallaudet is a predominantly white institution, and they felt, “Where in the curriculum can I learn about myself, as well as others learning about them as well?”

Ryan: Thank you so much, Dr. Carolyn McCaskill. You are leaving behind a huge legacy.

Carolyn: Thank you so much, and I couldn’t do it without support.

So thank you too, to everyone who has supported me, my department, the Center for Black Deaf Studies, for giving me the opportunity, really.

Why Black Deaf Studies matters: A defining moment

The creation of the Center for Black Deaf Studies and the launch of Gallaudet’s new minor in Black Deaf Studies set the stage for the center’s spring 2023 symposium, Why Black Deaf Studies Matters: A Defining Moment.

“Black Studies scholars will use a Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) lens to address the urgency for scholars to engage in the scholarly study of Black Deaf people to further advance the knowledge base of the field.

Deaf white scholars in the field of Deaf Studies to discuss the challenges that historically kept Black Deaf people on the fringes of academia.”

Sorenson is sponsoring the event, a continuation of its support for the Center of Black Deaf Studies. In 2022, Sorenson gifted a $3 million endowment to Gallaudet to support expansion of the center and its initiatives.

Louise B. Miller Pathways and Gardens: A legacy to Black Deaf Children

One of those initiatives is the creation of the Louise B. Miller Pathways and Gardens: A Legacy to Black Deaf Children, a memorial and walking path.

The project honors Louise B. Miller, a mother who sued the D.C. Board of Education in 1952 on behalf of her Black Deaf sons and other Black Deaf children whom existing law prevented from receiving an education in the District of Columbia, though white Deaf children could attend Kendall School on the campus of Gallaudet University. Her legal victory in U.S. District Court spurred the opening of Kendall School Division II at Gallaudet in 1953 for Black Deaf children and set the stage for Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case in 1954 that ended racial segregation in schools.

Celebrate Black Deaf history

Just like with any other cultural appreciation, how you celebrate Black Deaf history is up to you. You could do some research and meet the challenge we presented at the top of this page: name two influential or famous Black Deaf people. For example, Dr. McCaskill pointed out she was the eighth Black Deaf person ever to earn a PhD in 2005; do you know who was the first? It was Dr. Glenn B. Anderson, who earned his doctoral degree from New York University in 1982. Seven more Black Deaf scholars followed in his footsteps over the next 23 years. However, as Dr. McCaskill mentioned, a dozen more achieved that accomplishment between 2005 and 2022.

Learn Black ASL

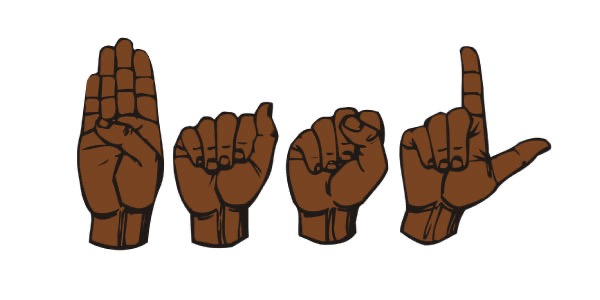

While Gallaudet University — the first and most prominent institution in the world dedicated to Deaf higher education — does not offer courses in Black American Sign Language (yet!), there are resources out there to learn the intricacies of Black ASL vs ASL. Many are informal guides on social media from individuals who use Black ASL themselves.

Black ASL is one of several dialects of ASL, just as there are multiple dialects of spoken English in the U.S. This isn’t unique to American Sign Language, either; for example, British and French Sign Language both have Black dialects as well.

Diverse sign language interpreting

Because Sorenson serves people from every regional and cultural background in the U.S. — and around the world, for that matter — our powerhouse interpreting team reflects a diversity of ASL dialects.

When scheduling Sorenson video remote interpreting or on-site interpreting services you can specifically request an interpreter to meet a variety of special needs, including race, gender, English/ASL or Spanish/ASL or trilingual, as well as specialized training for legal interpreting, Deafblind interpreting, language deprivation (Certified Deaf Interpreters), and STEM subjects.